Prisoners of War

The words “You are not forgotten” are prominently displayed on the black and white flag that honors American prisoners of war (POWs) and those in the military who became missing in action (MIAs). The flag is stark in its simplicity. In the forefront is a silhouette of a man’s head, bowed, in front of a guard tower and piece of barbed wire. Aside from the sentence “You are not forgotten” and the acronym “POW MIA,” no other words appear on the flag. Newt Heisley, who designed the banner, served as a pilot in World War II. While the flag itself dates from the Vietnam War, Heisley drew on his experiences in World War II to create the words and images on it. Heisley flew missions across the South Pacific in transport planes carrying men and supplies from one island chain to another. He traversed huge expanses of ocean. Heisley understood that sometimes planes suffered mechanical problems, lost power, and disappeared forever. More than once, he thought of what his fate would be if his plane went down and he became a prisoner of war. Heisley believed “the worst thing that could possibly happen would involve being taken prisoner and being left and forgotten somewhere.”

In spite of Heisley’s plea, one could argue that POWs and MIAs are forgotten in general histories of wars. If referred to at all, their stories usually stand on the periphery. In the first months of United States involvement in World War II, however, this was not the case. Accounts of Americans becoming POWs in the Pacific theater made newspaper headlines. In the days, weeks, and first few months after the December 7, 1941 attack at Pearl Harbor, the Japanese captured United States military and civilian personnel. These men, and some women, were stationed on Guam, Wake Island, and the Philippines, all of which were American military installations in the Pacific. Guam fell first. After two days of trying to hold back the enemy, on December 10, 1941 Japanese forces overpowered the five-hundred-man United States garrison on Guam.

These men, and five women who were military nurses, became the first group of American POWs to be captured by the Japanese.

On Wake Island, members of the military and civilians fought off enemy occupation for sixteen days, from December 8th until December 23rd. During that time, newspaper headlines likened the 1,600 defenders of Wake to the men at the Alamo.

In the Philippines, American Defenders of Bataan and Corregidor captured the nation’s attention from January to early April of 1942. On Bataan, a peninsula on the main island of Luzon, between 70,000 and 80,000 United States forces held off greater and greater numbers of the enemy. Of that number, approximately 12,000 were Americans, with the rest being Filipino soldiers.

By the beginning of March, about 250,000 Japanese had landed on Luzon.

Throughout the first months of 1942, American forces suffered the ravages of diseases such as malaria and beriberi. The lack of proper sanitation facilities led to large-scale cases of dysentery. The impossibility of additional supplies led to daily rations being cut again and again. Faced with such conditions, the United States military on Bataan was forced to surrender on April 9th. The next day, the Japanese demanded that Americans and Filipinos begin what would become a one-week forced walk out of the peninsula. It became known as the Bataan Death March. The destination was a prison camp about sixty miles north of the peninsula. Weakened by malnutrition and disease, many could not keep up the pace demanded by the Japanese guards. The enemy executed thousands where they fell.

As survivor Morgan Thomas Jones, Jr. described it, the March was “a brutality beyond belief.”

With the Defenders removed from the peninsula, the Japanese used its southern tip to shell the 11,000 American forces on Corregidor, an island south of Bataan.

As on the peninsula, outnumbered American forces were forced to surrender on May 6th. All four of these losses--Guam, Wake Island, Bataan, and Corregidor-- made the front page of stateside newspapers throughout the early months of 1942. If only momentarily, Americans focused on the POW issue. Overwhelmingly, these prisoners were members of the military. In contrast, the public knew little of the almost 14,000 American civilian men, women, and children captured by the Japanese on various islands in the Philippines and in a few other areas of Asia.

After Bataan and Corregidor, the Japanese captured other POWs in the Pacific, such as crewmen of planes that went down or sailors whose ships were sunk. But newspapers focused little public attention upon these individual losses. Additionally, Americans at home knew nothing of what happened to their countrymen, and countrywomen, once they were captured. Life in various prisoner of war camps became a special type of hell with scant food allocations and brutal treatment the norm. Most POWs held by the Japanese eventually ended up in Japan to work as forced labor. The trip to the home islands occurred on vessels dubbed “the Hell Ships.” Inhumane conditions on board resulted in even more deaths. Some who survived the Bataan Death March judged the voyages on the Hell Ships to be worse than the March. As the war in the Pacific progressed throughout 1942, United States forces assumed the offensive in places like the Coral Sea, Midway, and Guadalcanal. After the traumatic losses at Pearl Harbor, and the surrenders at Guam, Wake Island, and in the Philippines, newspaper headlines concentrated on United States victories, not defeats.

Once surrender occurred at those three Pacific bases, families of the men and women captured could no longer get information through the media on the status of those behind enemy lines. Even Washington D.C. could not answer the pleas of families for news of loved ones in that first year of the war. Only after the Japanese government supplied the International Red Cross (IRC) with names of those it held, did some families know if their loved one survived. Not all, however, received such information. This was true, too, for relatives of those who were lost as the war progressed. Throughout 1942, 1943, 1944, and most of 1945, families waited everyday for word of their loved ones and hoped they would come home. “Not knowing” haunted parents and siblings, especially the mothers. Unlike the families of POWs, the war took on a much larger dimension for relatives of other American military men and women. These parents followed the movements of large armies or navies across continents and oceans as the Allies made their way toward Berlin and Tokyo. They knew their sons were playing a role, albeit it a minor one, in such offensives. For the families of POWs, however, the focus was much more circumscribed, and the information much more limited. What these families went through must not be forgotten. In a way, though, we have lost forever their stories since the parents of the POWs are no longer alive. Our opportunity to capture their personal experiences, through their recollections, is thus lost to history.

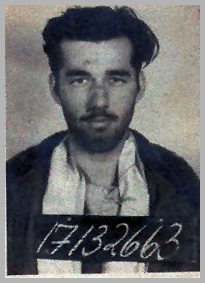

What follows are some stories of American POWs held by the Japanese. They are drawn primarily from firsthand accounts. Note that two mothers are also included. Both of these women saved personal correspondence, letters from the government on the status of their sons, and information they received from the Red Cross. The mothers carefully put all of these documents in scrapbooks that survive to this day. What they saved allows their stories to be told.

As the following pages detail the history of Americans held as prisoners of war, perhaps it is best to preface them with a question posed by one POW, John M. Wright, Jr. On the last page of his 1988 memoir, Captured on Corregidor: Diary of an American P.O.W. in World War II, Wright asked a question--“We knew what we had been through, but could an American at home ever be made to believe it?”